Killers of the Flower Moon and Other Misconceptions

Contextualizing U.S. history through archival artifacts and texts

It’s been a while! But here we are, and Wilderness is still here! The newsletter, I mean. I’ll be sending out a short post later this week to share this newsletter’s evolving ethos, but for now here is some scholarly work I’ve been doing with archival materials.

For the past few years I’ve been doing archival research— an ongoing project of trying to trace my own white ancestry, the colonization of the United States, and specifically how (mis)conceptions of Native Americans evolved from European point of contact. As a white American, I think it’s essential for us to understand not only the history of our country but also our white history— what led us here. This history has everything to do with current land practices in the U.S., as well as current fire suppression policy. Today’s essay is part of that work.

The title of this post refers to the film Killers of the Flower Moon, rather than the book. And I don’t really write about the film at all (sorry!). I only reference it. Please note that some of the content in this post engages with historical violence and genocide and may be disturbing.

(this post will be too long for email. better to click through before you start reading)

In autumn I took a trip to the Florida State University archives in the hopes of finding archival materials relating to historical perceptions of Native Americans particularly by white Americans and Europeans. In spring 2023, I had traveled to the Newberry Library in Chicago with the same project, although back then I was more focused on book research.

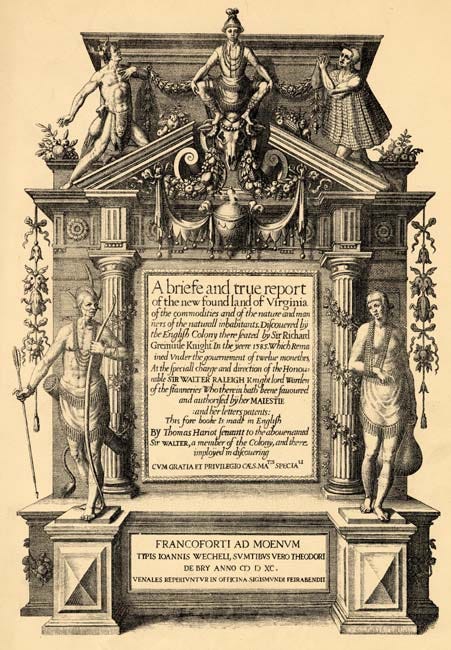

I began a line of inquiry I’d initially started after reading A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia, by Thomas Hariot. This text was composed in 1585, when Hariot accompanied Sir Richard Grenville to what’s now known as North Carolina from Britain, in a failed attempt to colonize the region (although, of course, the land was eventually colonized).

What interested me about Hariot’s “report” was its rhetorical positioning: essentially it was a pamphlet aimed at convincing English citizens to leave their home country and come to the New World, or at least invest in its development.

Hariot created a detailed taxonomy of the region’s resources, describing flora and fauna in commodified terms as well as listing and defining natural resources such as timber, copper, and silk. In writing about the Algonquians, whose language Hariot spoke, he described them as docile and open to religious conversion. The text was initially accompanied with sketches of the Algonquin people. Theodore De Bry transformed these sketches into intricate engravings. In doing so, he subtly changed the appearance of the Algonquians, lending them more European features. Whether purposeful or accidental, I consider this to be a visual representation of the ways in which Europeans projected their belief systems onto Native American peoples.

A Briefe and True Report is one of the earliest documentations of colonization in the United States, different than the journals and logbooks of explorers. Hariot’s depictions are blind to the richness of Algonquin culture— he writes that the Algonquins have no tools, crafts, or artistry, but that they “shewe excellencie of wit.” He remarks that they could be civilized and “brought to true religion.”

Like the plants, animals, and materials that he lists as commodities, he describes the Algonquins in terms of potential cultivation: they are good because they can be converted to Christianity, much like the land itself can be converted agriculturally. Hariot reduces the Algonquins from humans to matter, or object.

The text highlights a fundamental and well documented misunderstanding typical amongst Europeans: that Native Americans were savages, devoid of religion and culture. This misunderstanding unfolded into the concept of Manifest Destiny: the belief that the destiny of new settlers was westward expansion into land referred to as wilderness.

Because Europeans were, for the most part, incapable of understanding that the United States was inhabited by people who practiced sophisticated modes of agriculture, ownership, commerce, religion, and culture, they deemed Native Americans “savages.” This was how they rationalized land theft, murder, slavery, indentured servitude, and genocide. “This form of rationalization functions to erase the dynamic of human relations, a form of inter-subjectivity where two or more people respond to each other as equally human, mutually respecting the other's subjectivity.”1

As Roxane Dunbar-Ortiz points out in her book An Indigenous People’s History of the United States, similar modes of religious rationalizations were implemented in Israel, South Africa, Australia, and other countries throughout the world. The grounding theology in the United States, deeply influenced by Calvinism, is illustrated in the first seal of the Massachusetts Bay Colony (created in 1629), which reads “come over and help us,” pictured below:

During my trips to the FSU archives, I found three dime novels and placed them in time: the mid-1800's to very early 1900’s. I decided to examine some texts written in the time period between the last of the dime novels and Hariot’s Briefe History: essentially the 1600’s to the 1900’s, with the intention of tracing the ways in which writers, settlers, and government officials engaged with Native Americans specifically: how their encounters and narratives of their encounters changed and shifted. What’s written here is only the beginning of this exploration.

Dime novels were newspaper-like publications: fictional narratives primarily depicting stories of western expansion and white heroism, nearly always accompanied with at least one illustration (usually on the title page). Beadle and Adams dime novels, published from 1860-1889, were the most prolific, but other publishers, primarily out of New York, also published various dime novel throughout and beyond that time period.

I found three dime novels that engaged with Native American encounters; Injun Dick (Aiken, B&A, 1897), Brothers in Buckskin (Ingraham, M.J. Ivers & CO, 1902), and Young Wild West: Cowing the Cowboys (author unknown, Harry R. Wolff, 1917). I was unable to find earlier editions of any dime novels in the archives, unfortunately. These three novels all depict stories centering whites, often of middle to lower middle class. Though the whites within these narratives are vary in their adherence to moral codes (some are savages, some lawful, and everything in between), Native Americans are consistently portrayed as savages, entirely unlawful. In the novels I read, none were named, while white men in lawful roles were given names such as Cheyenne Charlie and Moccasin Matt, almost mirroring ideas of Native American nobility. In Brothers in Buckskin, Moccasin Matt, a lawful character, and “Major,” another white character, happen upon a collection of bones and skulls in the desert:

“Moccasin Matt smiled almost sadly.

‘I had a hand in fixing ‘em myself. I have a reason to remember this place. Twelve of us, prairie rangers every one, held out against three hundred Indians for three days,’ he said.

‘Indeed. Then these bones out yonder—’ ventured the major.

‘Are Indian bones. You’ll find ‘em all around the place...these reds were wolves; they wanted blood.’”

This was the most interesting moment I found across all three novels featuring Native Americans. The scene demonstrates what was, by the 1900’s, a common assumption about Native Americans: that they were inherently violent and comparable to animals. In reality the likelihood of an encounter with 300 Native Americans in the early 1900s was quite slim— many tribes throughout the United States had been vastly diminished in numbers. Even when tribal numbers were higher, encounters with Native Americans rarely led to violence without provocation by whites. But of course the novels were not married to accuracy, and nor were the perceptions of whites.

My primary question is, were whites capable of accurately seeing Native Americans accurately at all?

In his book Vanishing Americans, Brian Dippie defines a cultural shift in perceptions of Native Americans occurring in the thirty years between 1830 and 1860, heralded by George Fennimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans in 1826. Dippie argues that, prior to the 1830’s, perceptions revolved around cultural assimilation, but throughout this time period violence towards Native Americans increased, as did the rationalizations for violence, in order to acquire land. The United States government increasingly passed laws legalizing the murder of Native Americans who refused to abandon their cultural heritage and lands (as did many states).

If we can understand the dime novels within the frame of this historical context, it could be argued that they were promotional materials rationalizing Native American genocide past, present, and future, all under the guise of heroic wild west narratives.

But organized warfare against Native Americans had been ongoing well before the mid-1800s, as were the Spanish Mission systems in California; the latter began in 1769 and lasted until 1833. The Mission systems implemented some of the most horrific violence against Native Californians well before the publication of The Last of the Mohicans, but they were, in a way, a precursor for the westward expansion narratives of the dime novels. The Mission system ended before gold was struck in Coloma, CA in 1848. The discovery of gold and resulting gold rush greatly accelerated the settling of the western United States and the genocide of California Indians, as well as the mounting rationalization of that state-sanctioned genocide. This time period is still currently romanticized in the United States, and few people know the details of the California Genocide, which (in my opinion) should be common knowledge.

But not all texts perceived Native Americans as subhuman.

In 1784, almost exactly 200 years after Hariot’s trip and 204 years after the publication of A Briefe History, the French-American Quaker abolitionist Anthony Benezet wrote Some Observations on the Situation, Disposition, and Character of the Indian Natives of this Continent. The document is remarkably progressive given its time period. Benezet directly addresses his reader, asking early on: “Is it not notorious that they are generally kinder to us than we are to them.” Initially his appeals are general, making a case for all Native Americans. As the book progresses, he gets more specific, outlining the role religion has played in their manipulation:

“The different denominations of Christians have rather added fuel to this false fire, by inciting the poor Natives, when it has suited their political purpose, to violence amongst themselves, and to become parties in the wars they have waged against one another.”

Benezet further zooms in, recounting a specific incident now known as the Moravian Massacre, describing in detail how the Moravians (Lenape and Mohicans who had converted to a pacifist mode of Christianity), were forced to relocate after refusing to fight on either side of the Revolutionary War. Although the Moravians begged to harvest their corn before leaving their villages (and were denied), they left peacefully. Imminent starvation compelled them to return for their crops. Many of the harvesters were women and children. The white men from nearby towns called them in for what Benezet called a “friendly meeting,” then violently seized and bound them, telling the Moravians, “their troubles in this world would soon...end.” The Moravians sang hymns and prayers and did not resist, refusing to stray from their pacifist belief system, even as the white men began slaughtering them.

This story was relayed, writes Benezet, by two surviving Native children; one of them having been survived a scalping (a practice performed often by white people on Native Americans, despite being historically portrayed as a tactic only used by Indians. Before their deaths, the Moravians were forced to disclose the locations of their other tribal members with the knowledge that they would also be slaughtered.

After this recounting, Benezet cites the story’s false representation in the April 17th, 1782 Penn Gazette, which reported the Moravians as “stealing a large quantity of provisions to supply their war parties” and the white men of stealing back their “plunders” from the “warriors.”

Benezet emphasizes that not one white man died in this incident, and that the report itself led to another attack on the pacifist Moravians. Benezet writes: “We are in a state of alienation from God,” and calls out the British and French in their hypocritical expressions of horror regarding “cruelties exercised by the Spaniards upon their Indians without considering how far ourselves are in a degree guilty of something of the same.” Without the Indians the English “must have otherwise perished” when first arriving the New World, he concludes, emphasizing how the very country’s colonization would have been impossible without the help of those they had slaughtered.

Benezet’s writing is free from any indicators of Native American dehumanization. Is this because the “Moravians” of whom he was writing had already converted to Christianity, or was he truly progressive beyond his era? The latter may be true, as he also fought for the freeing of Black slaves and started a school for freed slaves in Pennsylvania. Benezet paints the Indians as neither savages, nor as patently noble, but as human beings.

This artifact is the only I came across that appealed for the full recognition of Native Americans as equal to whites, although my time and energy were limited and I’m sure there must be more (I hope so).

Given the events dealt with in Benezet’s appeal, I am not entirely on board with Dippie’s argument that perceptions towards Native Americans only began shifting around 1830. Clearly these Moravians had converted to Christianity, and yet they were slaughtered and vilified. Yet narratives were undoubtedly shifting during the 1830’s— my question is whether or not one can pinpoint this shift to a time period at all. Were Indians at any point not slaughtered, whether they converted or not? And what about the illnesses brought by whites (something Hariot describes in his text without ever acknowledging outright)? It all feels rather slippery.

Around fifty years later, in an 1832 text called Adventures on the Columbia River, Ross Cox recounts his western travels during the early 1810’s, as he searched for goods with the North West Company (dealing in furs). It was written 15 years after he had emigrated back to Ireland, and therefore his documented experiences occurred about thirty years after Benezet’s text was published.

In its preface Cox references Chateaubriand, who wrote a romanticized narrative called The Natchez : an Indian tale (published in 1827), writing that in his own travels, he (Cox) “did not meet with any tribe which approached that celebrated writer’s [Chateaubriand] splendid description of savage life” because, essentially, the “savages” he (Cox) encounters had already been “contaminated” by the white man. This is strange to me, because Chateaubriand was documenting his eastern travels during the late 1700’s, and there are only twenty years between his travels and Cox’s. One could surmise that Chateaubriand was more willing to romanticize the Native Americans he encountered, whereas Cox writes that he is “compelled by truth” to portray his encounters “accurately.”

In Adventures on the Columbia River Cox divides Native Americans into two binary categories: noble and defiled. He wants Native Americans to inhabit the identity of the Noble Savage, which I’ll loosely define here as Indians living in a state purely connected to nature; nature then perceived as primitive compared to the more sophisticated ways of whites, but also free from white influences.

It’s an impossible category for anyone to inhabit, partially because whites mistakenly thought “nature” in the U.S. was wild, rather than an intentionally cultivated landscape, and viewed themselves in opposition to the “savage” living in nature.

Nonetheless, Cox primarily describes Native Americans in disgusting, racist terms. Upon his arrival by ship to the Columbia river he sees “the most repulsive looking beings that ever disgraced the fair form of humanity.” Cox expects these “beings” to be violent, but they aren’t— this expectation of violence despite its absence is repeated throughout the book. Cox assumes that Native Americans are inherently violent, despite being constantly proven otherwise. When he does encounter violence (often defensive), their violence serves to prove his assumption of their innate violence.

Throughout his travels Cox and his company obtain food, canoes, tools, and guidance from the Native Americans they encounter, yet he never observes this friendliness as innate. Several times he compares Native people, even children, to snakes, and uses “snake eyes” as a descriptor. The only Indians who escape his subhuman observations are the ones who have retained the totality of their culture— those who adhere to his expectations of what a Native American should be— an inherently false perception.

One could wonder at what prompted Cox to write his memoirs and publish this narrative when he did. The Last of the Mohicans was published six years before Adventures on the Columbia River. Because Cox also mentions Chateaubriand, my assumption is that Cox wanted to write a “real” narrative of Native Americans, one that isn’t romanticized and that perhaps paints a more negative (or realistic, in his perception) picture of Native Americans. Likely he was disappointed that the Natives he encountered were different than he’d expected. His experience mimics that of John Muir, who, as M. Kat Anderson notes in Tending the Wild, “was clearly troubled by the Indians he encountered...he wanted them to be natural, like animals, but they disappointed him by showing some of the qualities he disliked in his fellow whites.”

This may explain why, in the dime novels, lawful white characters were given names associated with Native Americans, while Natives themselves remained unnamed (unless they were “mixed-blood”), almost as if they were simply part of the wilderness backdrop. In the dime novels, there are also roving groups of savage white men, but even they are placed higher in value than Natives, who are portrayed as they were in Cox’s narrative: inherently violent, untrustworthy, and defiled. Perhaps in the earliest dime novels there were more “noble” portrayals of Native Americans, but in the three that I engaged with, there were none. White men were heroic. Natives were “like wolves.”

We can contextualize this in terms of both the exploitation and genocide of Native Americans but also the conservation movement initiated by men like Muir and how nature, in its romanticism, was separated from civilized (white) humanity. This separation led to land being stolen from Native Americans and handed over to government agencies in order to conserve and preserve resources (or sell it to settlers). Muir, along with many other conservationists, used words like Edenic and pristine to describe these “wild” places. Nearly all whites colonizing the U.S. were completely blind this pristine land being influenced by its inhabitants. They couldn’t see the alternative modes of agriculture and land tending because these modes strayed from their narrow European conceptions of civilization.

Yes, the conservation movement was clearly necessary (the lands would have been taken either way, and without conservation they would have been completely pillaged), but it also commodified nature as “resources,” which, in the bounds of this paper, we can trace back to Hariot’s Briefe and True History.

Texts like Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Song of Hiawatha (1855), and Zane Grey’s Spirit of the Border (1906), amongst many others, either repaint history through the white gaze in sensationalized terms, romanticizing violence and casting white settlers and armies as heroic (as Grey does in his recasting of the Moravian Massacre), or portray Native Americans as noble savages; people who are categorically one with nature and morally pristine, which erases their complexities as well as their own cultural, agricultural, and religious sophistication and inevitably leads them to be stained by white culture, and therefore defiled. Either way, Native Americans are monochromatic and dehumanized, and the European and/or American white man is cast as superior, either on moral terms, by proxy of land inheritance, or, in the case of Song of Hiawatha, by successfully converting the Indian to their supposedly superior religion.

The dime novels further flattened these tropes and accessibly reproduced them for whites who were literate but had only a dime to spare. As texts, they drew settlers west for adventure and intrigue, ultimately helping settle the land already occupied by Native Americans, inflicting increasing levels of violence onto tribes and Native individuals. They also set the stage for western films which reinforced these tropes and further romanticized western settlement.

I feel as if I have just touched the surface of deep waters, and I look forward to pursuing this line of inquiry further. As a white person who writes fiction and nonfiction, I ask myself if any fictions or nonfictions written by whites can accurately portray Native Americans, especially as scholars, cultural critics, and Native Americans interpret and discuss the new film by Martin Scorsese, Killers of the Flower Moon. Some Native Americans have criticized the film while others heap on praise. This “some” and “others” is also a binary: it positions Native Americans as a monolith and divides them down an imaginary center, when reality asserts that discussions surrounding any text, by any group, are always more complicated. So, maybe it’s in this spirit that I consider my own writing and scholarship— a commitment to exploring complexity, which makes any declared conclusion or generalized assertion nearly impossible.

Thank you for reading Wilderness, and I hope this was illuminating and/or thought-provoking.

Let me know your thoughts in the comments.

Gohar, Saddik M. "Navigating the colonial discourse in Fenimore Cooper's The Last of The Mohicans." Forum for World Literature Studies, vol. 8, no. 3, Sept. 2016, pp. 446+. Gale Academic OneFile, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A496133809/AONE?u=tall85761&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=7018f6e9.

Thanks for this. I live in the Puget Sound region. I did a little research on white interactions with Native Americans here for four-part series I did on land ownership and the family farm as a colonial concept: https://johnlovie.substack.com/t/land

Echoes of the gold rush and the nineteenth century still echo. Much of the land here, after being stolen from the Native Americans, was sold to people who had made their money from the gold rush. Many of their descendants still own that land today, and that history still defines the land use patterns.

And that concept of wilderness just will not go away. I cringe now every time I see a "Wilderness" sign when out hiking. It's a raw reminder of who is being left out of the story.

I appreciate your scholarship here and look forward to reading more.

Thank you for your hard work.