Texas Wildfires and Why Dying Trees Might be a Good Thing

Holding on to hope as the world continues burning

Dear Fires Readers,

It’s been a while since I’ve just sent a thing out without it being an interview. Before I get into it I want to tell you that I’ll be releasing a wonderful interview with Zeke Lunder next weekend for subscribers. Zeke has been waiting patiently for me to release our interview from forever ago!

Texas is Burning

There are several fires burning across Texas— the largest about 100 miles west of Fort Worth. The Eastland Complex is a conglomeration of several fires and has resulted in the death of one Sheriff’s Deputy, Sgt. Barbara Fenley whose vehicle veered off the road in smoky conditions. She was on her way to help an elderly resident evacuate. The fires are actively burning in thick brush and underbrush as well as timber.

Firefighters are hoping that an incoming rain storm with be enough to stop the fires, though accompanying wind could have the opposite effect. The rain is only expected to last one day, while windy weather continues.

Two firefighter were injured on Sunday while fighting the Big L Fire, which was ignited that same day, along with the Blowing Basin Fire. Both fires are now part of the Eastland Complex.

The landscape wherein these fires burn is mostly rolling, grassy hills, brush, and some timber. Many agencies in Texas implement prescribed burning, but prairie land needs to be burned every year, and much of the land has been succeeded by non-native species due to the absence of fire. Putting more fire on the ground in Texas could reduce the instances of volatile wildfires and promote the growth of native grasses and brush, which is more fire resistant. Cedar, locust, and persimmon are all invasive species. Invasive grasses, such as cheatgrass, are better carriers of fire than native grasses, and therefore promote more volatile wildfires.

According to Texas Parks and Wildlife, the best time for burning in this area is after leaf drop and before the winter rains. With climate change, it can be difficult to gauge how plentiful the winter rains will be, but burning will help to encourage the growth of native species, which also increases insect populations and, in turn, increases habitat for native ground fowl.

We’ve Taken Trees For Granted

A recent Guardian article takes an alarmist tone. The title; Is this the end of forests as we’ve known them?, is, of course, sensational. I honestly hate it. I hate that, as readers, we’re yanked around by our fear and foreboding, and the media promotes and embraces this.

Here’s my opinion: I don’t think scaring people with ominous headlines spurs real change. That said, the article is worth reading, though one’s eye should be aimed towards deciphering the rhetoric (SCARY THINGS ARE HAPPENING) from the story. Once you scroll past the rhetorical terror, you can find this gem:

“Researchers acknowledge that there is considerable ambiguity in their predictions about tree mortality. For one thing, it is unclear how many of the trees now dying essentially weren’t meant to be there in the first place. Western forests are denser than they were historically because of human influence: the practice of tamping out wildfires, beginning in the early 20th century, has interfered with a natural process in which blazes weed out younger trees and undergrowth.”

Imagine this: We have too many trees. We’ve promoted the growth of trees and called them sacred, above prairies, which are superior carbon capturers. Just read my interview with Lenya Quinn-Davis to understand that trees are not the answer to our problems, and they never were.

When Europeans arrived in the United States, they found open, expansive forests whose trees were widely spaced and gigantic (there are a few exceptions to this but this was how most forests looked) and wide, open prairies. Many explorers and colonizers called the land they happened upon “park-like.”

As Europeans settled across the United States, displacing Indigenous Americans, they removed fire, and trees sprouted. Somehow, naturalists like John Muir and Gifford Pinchot linked the word “wild” with “untouched” and set aside forests for logging and wilderness while prioritizing the suppression of fire.

If we reframe our view of fires, of bark beetles, of forest holocausts and dying trees, then maybe we can see that these things are naturally working to balance out what we have disturbed over time. Diana Six, an entomologist, has done some great work with bark beetles and this TED Talk is a must watch when it comes to understanding how beetles function much like fire in our forests. While you’re on YouTube you can watch this TED Talk by Camille Stevens-Rumann, who was quoted in the Guardian article.

It’s funny: I’ve pitched pieces to publications about our excess of trees and the toxicity of John Muir’s messaging, and no one’s biting. And digging into this article, it’s clearly about how nature in out of balance, rather than climate change’s catastrophic effect on trees.

My question is: are trees increasing the pace of climate change in their excessive water consumption? Is part of climate change the absence of fire rather than the presence of it?

Justin Trudeau once claimed we should plant a billion trees to prevent climate change, and he’s over 8 million trees closer to that goal. But planting that many trees would be catastrophic. North America as a whole is deeply uneducated when it comes to fire and ecological health— we’ve been brainwashed to think that fire suppression is the ideal, and thick, overgrown forests are healthy.

It’s the opposite.

To battle climate change, we must put fire on the ground.

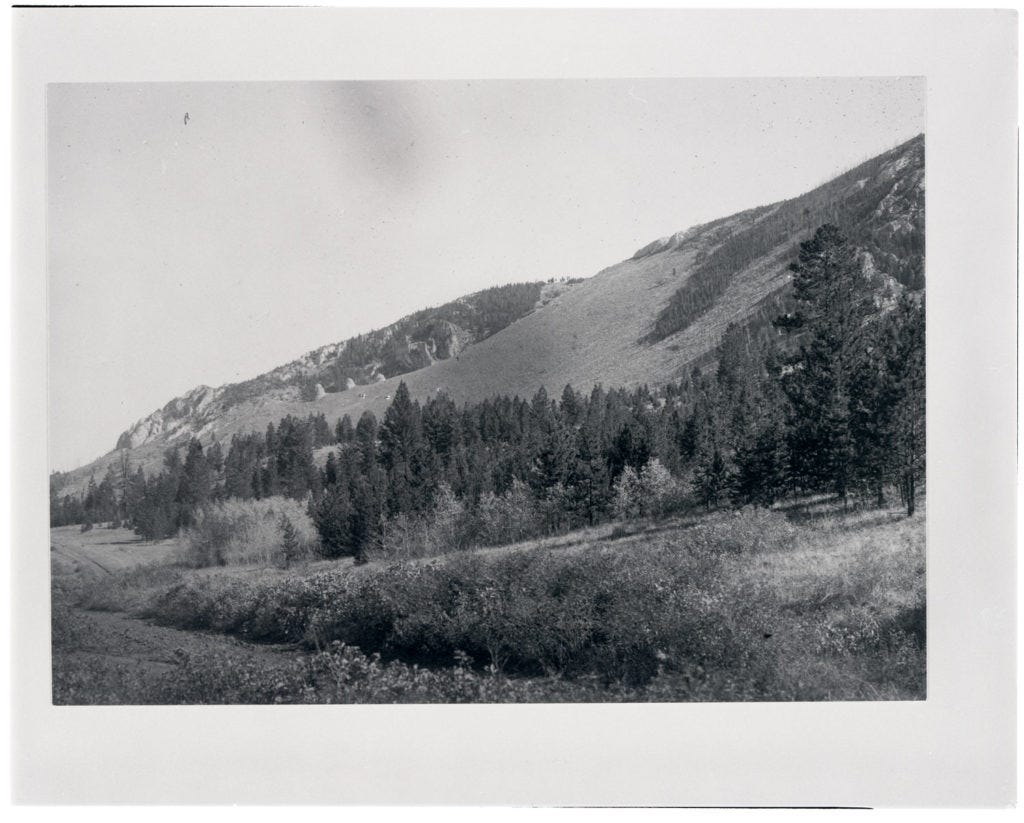

These pictures and more can be found HERE.

Policies related to the "protect and preserve" mentality grew out of romantic era writings dating back to the 17th century which were not based on science or an understanding of the various ecosystems that European conquest came across. Most of the peoples in these new lands were considered to be privative stone aged peoples, sadly a mythology carried forward by anthropologists up until the last few decades. Omer Stewart was one who tried to bring forward the concepts of Indigenous burning practises but his works were heavily suppressed by his peers. Henry T. Lewis and Kat Anderson published his papers in a book called "Forgotten Fires", well worth the read if you can find it. Lewis and Anderson have both published excellent research related to the subject. Lewis had made a 16mm film called "The Fires of Spring" back in the late '70's, early 80's. He had digitized it and was re-editing it when he passed on. I was able to post the edited version on YouTube. You can view it here.... https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XX0rhYqkC4Q PS, in your photos, you referenced "less than a decade", did you mean less than a century?

Super interesting. I'm constantly blown away by my pre-conceived notions of what forests/landscapes *should* look like when I learn more about things like high-severity fire regimes, the historical precedence of stand-replacing fires and how in many places (northern, east slope Rockies especially), regular fire historically maintained prairies and shrublands that have since become densely forested. Thanks for a thought-provoking read.