An Interview with Lenya Quinn-Davidson, Director of the Northern California Prescribed Fire Council

Part one of two

About two months ago I had the pleasure of speaking with Lenya Quinn-Davidson, director of the Northern California Prescribed Fire Council. I’d heard Lenya’s name several years ago, when I was in France researching and starting to write my book HOTSHOT (which will eventually be published). Lenya is part of the prescribed burning renaissance many communities are experiencing in California.

This renaissance, led primarily by Indigenous Californians (read my interview with Frank Lake), has given me a lot of hope, but faces much resistance from uninformed parties; most recently Rep. McClintock and Rep. Lamalfa of California, who just yesterday introduced legislation demanding full suppression of all fires on Forest Service Land. Enacting this type of legislation could have a disastrous effect on forest health and communities.

I spoke to Lenya over Zoom, sitting my apartment in Seattle. She was in Eureka, looking out over the ocean.

This interview is broken up into two parts because of its length. If you feel like you learned something here, please share it on social media. Screenshots, quotations, and forwards are greatly appreciated!

Stacy: I think it would be great just to start with kind of how you got into the work that you do. I think also, just especially as a woman, I think, I worked as a hotshot in the early 2000s, mid 2000s, and I feel like fire is not necessarily always an easy place to be if you identify as a woman or if you're not a man. So I'm interested to hear about your journey and how you got there.

Lenya: “Yeah. I kind of took a different path because I never worked in wildland fire. I never worked in fire suppression. So I came to this work through restoration, through working in restoration. When I was in undergrad, I was more focused on watershed restoration and I took some classes, some fire and forestry and forest science classes. But my real focus was on stream and watershed restoration. I worked for about four years for a stream restoration company, both during college and then after college. And ultimately decided that I wanted to get out of the creeks and do more in the uplands. I was more interested in land management and fire. So I went back to grad school and focused on prescribed fire, and on impediments to prescribed fire.

That was up here at Humboldt State for my masters. Through that work I got involved in some fire ecology research. I spent time in Florida doing prescribed burning as part of a research project, then I ended up working for California State Parks for a little bit and doing some burning in that job, then ended up at University of California where I became the fire advisor. During my time in grad school, we formed the Northern California Prescribed Fire Council.

I never worked as a firefighter. And so my experience has been a little different than yours. Though I work a lot with women in fire and you probably know that I'm the lead organizer for the WTREX, which is the women in fire prescribed fire training exchange. So I'm very familiar with all those issues, but thankfully never really went through that myself.”

Stacy: “So you worked in Florida with prescribed fire. There's so much focus on prescribed fire on the west coast, yet there's so much fire-adapted land in the south and Southeast, and even in New Jersey, like areas that are still being burned regularly. And so I'm interested in how that has informed and continues to inform the work that you do at West.”

Lenya: “I only spent about four months in Florida but I would say it definitely informs my work. I hosted WTREX there in 2019, too, and went back there. So I spent a couple chunks of time burning in Florida.

“I think we have so much to learn from Florida. There's a comfort with prescribed fire, and not just from the public, which I think is cool, but also the practitioners. It's interesting, what I always say in California and in the West is we just really don't have people who are doing this a lot, enough to be truly comfortable with it. So even our most experienced prescribed fire practitioners in California may not actually be very comfortable with prescribed fire. They're more comfortable in a wildfire scenario. That's what they're more used to and they kind of tend to conflate prescribed fire with wildfire. So I think there's a central fear and tension around prescribed fire in the West that comes from this fire suppression culture that we operate under. And when you go out to somewhere like the Southeast, they are really operating in more of a prescribed fire culture. Most of their experience with fire is through prescribed fire and they don't have as much experience with wildfire. So they're not tainted in that way.”

And it's interesting when you talk to people out here, they'll be like, we can't burn. It's so different. It's different here than Florida. The landscape's different. It's steeper. It's more complex. But to me, the difference is really in the social framework and the attitudes and just really that comfort.”

“I know some prescribed fire practitioners in the Southeast who burn 100 days a year. They're out on the ground, prescribed burning 100 days a year.

Imagine if you did anything 100 days a year how good you'd be at it, how nuanced your understanding would be, and how intuitive it would become for you. I'd say the top prescribed burners in California are maybe burning 10 or 15 days a year. There may be a few that burn more than that. Most people I'd say burn far less than that. Maybe even only two or three days a year. You can't be really good at something if you're not, if you're only doing it 10 days a year. If I say that to people on the west coast, and I'm counting myself in that too, people get really defensive because they don't want to think they don't know prescribed fire, that they are not comfortable with it. But I'd say for the most part, it's true.”

Stacy: I definitely agree with that from my experience. And as a hotshot we burned all the time, but it was always in a context of suppression. So it wasn't with any sort of ecological outcome in mind. We would just light it up.

Leena: Yeah.

Stacy: I think the difference between that and between a very deliberate prescribed burn, which is seeking certain outcomes, it's incomparable because, yeah, it's just totally the only way that that kind of experience can lead to an interpretation into prescribed fire is that you see how fire moves on a landscape. But that's still...

Leena: Yeah. It's still valuable, but it's not. In the prescribed fire world, we talk a lot about the art of prescribed fire and those burnout operations are not probably as artful.

Stacy: No. Not artful at all.

Leena: It's got consequence too, right. If you're operating in a wildfire environment and something slops over (when a fire goes out of bounds) or whatever, no, it's low consequence-

Stacy: Totally.

Leena: In a prescribed fire setting, you're so carefully planning and coordinating all of that. And so, yeah, I think it's totally different, but like you said, there's learning to be had in that setting, but it's not the same.

Stacy: Yeah. And as far as why folks have so little experience in the West, would you say that it is because of the culture surrounding wildland fire and the barriers that people have to get through? Because I've spoken to Will Harling and Frank Lake and some other folks, but I think from talking to people, there are just so many barriers. And I know you've written about this too. Barriers to prescribed burning that just make it almost impossible for people to get extended experience with burning. And I don't see it as a difference in ecology because Florida is a very flammable and highly populated place.

Lenya: Yeah.

Stacy: It's not, it's even more flammable than...

Lenya: Yeah. They have much more volatile fuels than we do.

Stacy: And they have tons of people living there. So really it's kind of, yeah. I really am interested in comparing those two and seeing how doing so could lead to increased burning in the West. Do you know what I mean?

Lenya: Yeah. Did you see the NPR story on that topic? When was that? This summer. Here, let me see

<iframe src="https://www.npr.org/player/embed/1029821831/1032738437" width="100%" height="290" frameborder="0" scrolling="no" title="NPR embedded audio player"></iframe>

Lenya: So that article quote, it's me, and then my colleague Morgan Varner, who is he and I co-founded the Northern California Prescribe Fire Council actually. And he is back in Florida now and works for Tall Timber Research Station.

We talk all the time about the need for an exchange program, if we could get Florida fire practitioners out here to burn with us and then bring Californians there. And the Prescribed Fire Training Center does some of that. That brings people to Florida to train. But I think even some kind of like sister program where we can start to do some of that cultural sharing and infuse some of that comfort here would be really cool. But people are so, California's different. I'm like, you guys were not that different. We like to think we're so different, but we're really not. We have so much low hanging fruit in California; Woodlands, and grasslands, and areas that have been treated. And we're not doing it. So it's like you said, these are all social. They're all people problems. They're not ecological or operational.

Stacy: I feel like so much of the problem or part of the problem with prescribed burning in the West is this one and done mentality of just, we burn off this area and now it's done. And this idea, like even with the new infrastructure bill and some of the language there about how fire is going to be used on landscapes and funding that's going towards that, we'll treat this many, this much land, but it needs to be about a continued engagement with.

I felt really frustrated reading that infrastructure bill, because it felt like some steps forward in some ways, but the language around it is just so much of the same old stuff about, we're just going to take care of this. We're going to do this. And it's like, no, it's about developing an ongoing relationship with these landscapes.

Lenya: It's about stewardship. I think a lot of times we think we can just throw money at problems and that'll fix it.

“This is about investing in people. It's not just about acres. Like you said, everyone wants to know how many acres a year should we be treating. And I'm like, I don't even want to talk about that. I'm not interested in acres. It should be about how many people have jobs in stewardship and how many facilities do we have to process material that comes from projects? And yeah, how many people are certified as burn bosses and feel supported in their work?”

Stacy: It's hard because it's an entire paradigm shift. I think that what I’ve come to terms with is that this kind of change won’t come from the top down, or from any sort of infrastructure bill or forest service or park service or any of that. That's been kind of challenging for me to wrap my head around.

The kind of work you're doing and the kind of work a lot of smaller organizations are doing, I feel like it really pushes these government agencies towards change and pressures them. So I have a couple things I want to address just about the ecological situation in California with fire and climate change, et cetera.

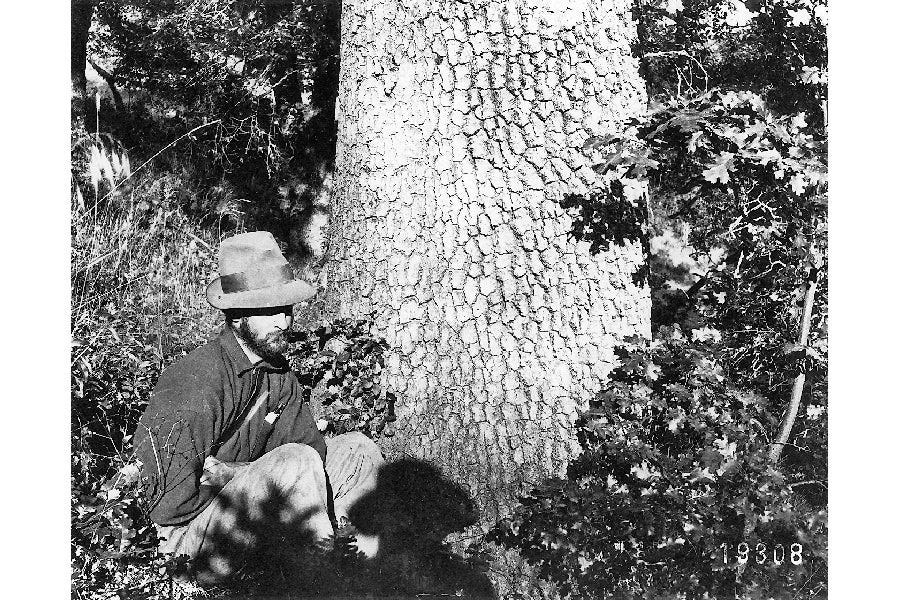

I feel like some things that get left out are the things we're actually looking for. The outcomes we're actually looking for. I saw that you've written about conifer encroachment and black oak. I'm interested in what we are actually looking for as far as restoring these places and spaces and what that would look like if we were able to do that. I thought that black oak would be a good starting point because that's a species that's so important too in some indigenous groups and acorns are so important. So yeah, I'm interested in what your thoughts are on that.

Lenya: "In general, I do think we should be motivated in our land management.

I think we should own the subjectivity of land management and the fact that we're making choices every day that are dictating what we're going to have into the future.

This whole notion that nature is separate from people and if we just leave nature alone, it'll be great. It’s so passé. I think we really need to say: no, actually humans have been making choices about what the landscape looks like for millennia. We've been making really subjective choices about what we want to persist on the landscape and what we care about. And we still are. There's no such thing as nature. We're part of it.

I work a lot on Oak woodland restoration. I'm passionate about that and people are funny about it. They'll say, why would you want to remove the confers from the Oak Woodlands because isn't that just natural? It's just natural succession. Well, it's natural in the absence of fire or in the absence of people managing for Oak Woodlands, which is the whole reason we have a lot of our deciduous Oak Woodlands in the Pacific Northwest; because people have maintained them.

“In the absence of people, those habitats wouldn't be here. It doesn't matter what's natural or not or whatever. It's really like, we care about those landscapes because they have crazy amounts of biodiversity. They're important for tribes and cultural practitioners, but they're also important for ranchers, and they're important for deer, and they're important for biodiversity and wild flowers.”

There are so many reasons why those habitats matter to us and to the things we care about. That's why we want to mention it doesn't matter if it's natural.

As we look toward the future of dealing with these fire issues, we really should own that and say, actually, you know what? I really care about that. And I want to see that. I want my grandkids to see those Oak Woodlands or I want my grandkids to know what a coastal Prairie looks like, because guess what? We're losing those two. And we're losing forests. Our forests are transitioning to Chaparral because of all the high severity fire. So we're losing those too.

That's what frustrates me about some of the environmental movement right now is, there's this kind of far extreme environmentalism. That's promoting this idea of no management and high severity fires spread. And it's like, what do you guys want? They're still stuck on that nature narrative that I think is unproductive and deeply problematic. And obviously borders on racism too, and history denial and things like that. But really I'm like, what are you guys going for? You just want like a bunch of fields of shrubs? We're losing everything we care about.

Stacy: I agree with all of that. I think one of the first things that I learned when I was doing research for my book, because I came into this research very much just as an environmentalist, as a lifelong environmentalist and a former firefighter who lived under that umbrella, but rejected the macho firefighting culture, because it had harmed me.

One of the first things I learned was that my idols of naturalism were actually perpetuating toxic narratives of people like John Muir, who brought his racist beliefs about native Americans and how they were supposed to look, how they were supposed to be inside of nature. This idea that nature was something to witness, and this blindness to people's effects on nature. Whether it's an effect of stepping back and leaving it alone or an effect of being interdependent.

This idea of succession and the way that our landscapes are changing is really toxic because it's all about leaving it alone. But also just also this idea that we need to plant a bunch of trees. 'm interested in what your thoughts are on that too because I think that through what I have learned in my layperson studies is that trees are not as great as we think they are. I've learned that grasslands are a better carbon sink than trees, and how much was done to nourish and perpetuate the presence of grasslands and prairies throughout California and the West, and how good that was for the land.

I'm a very visual thinker. So as I speak, I can see in my mind the beetle eaten forest, and things like that. To me, just from what I've read and through the work of Diana Six and people who are doing work with beetles and saying: that's actually happening for a reason.

“These trees are disappearing for a reason; because no landscape is meant to support that many trees.”

Lenya: Yeah.

Stacy: I'm interested in your thoughts on that. Especially for my newsletter readers, just helping to kind of dissolve this narrative that forests are the answer to everything and that we just plant more trees and the earth will be healthy.

Lenya: Yeah. Totally. I think there's an interesting psychological study to be done on people's obsession with trees. You go to those events where they're handing out little Sequoia trees or something for people to take home and plant and I'm like, why would you do that? They're not going to go in the right location.

My mom is really into trees and she's planted all kinds of trees. I grew up in a valley bottom in Trinity County in East of here. She planted so many trees in the time she lived there and we got these weird Cedar trees that she planted out in the field.

There's this group of blue spruce trees that she planted, and she loves them. She’s awesome, and I have made fun of her for this. he's awesome. It makes people feel good to plant trees. But it's bizarre.

Last weekend I was at a workshop with the California Indian Basketweavers' Association. One of the presenters was talking about how one of the main goals of their land management is to check succession. That's what they did with fire. They were always checking succession in the Oak Woodlands and in the riparian areas for a variety of reasons. People are so stuck on this narrative of stand back and watch nature. And a lot of it is about trees.

Now here we are in this situation where we have way too many trees.

One of the things that I'm researching right now, from a project in Oak woodlands looking at the water demand of all these approaching conifers.

Anecdotally, if you talk to folks who have lived on these landscapes for a long time, a lot of the ranchers who I work with and stuff, they talk about how so many of their springs have dried up. The springs that used to feed the trough dried up 10 years ago and never came back. Not related to drought. Related to the water demand of all the extra vegetation that's on the landscape now.

I called that project Silent Straws. If you imagine how many extra trees are growing throughout the landscape, the amount of groundwater they’re using is mind-blowing. Simultaneously we have climate change and drought. I think the answers to all these questions are so interwoven. We don't hear about that a lot. You talked to Frank (Lake) so that's great, because he talks about that part.

TO BE CONTINUED NEXT WEEK…